All fields are required

There is another outbreak of E. coli linked to romaine lettuce. The CDC warned consumers not to eat any romaine lettuce from Salinas, Calif., after at least 40 cases of E. coli infection nationwide were linked to contaminated products from that region. … also advised retailers not to sell any lettuce harvested in Salinas. This means, there is likely to be a romaine lettuce E coli outbreak lawsuit. More than one romaine lettuce E coli outbreak lawsuit has already been filed this year, as a result of the outbreak this past spring in which 210 people were infected with E. coli. “It’s scary when E. coli contaminates a ready-to-eat food, like romaine lettuce. Lettuce is supposed to be safe to eat. But as a consumer, you can’t tell whether your romaine lettuce is safe. You can’t smell, taste, or see E. coli bacteria. They’re so tiny that they are invisible. This is why it’s so critical that the companies who make our food make sure that it’s safe before they sell it to us,” says E. coli lawyer, Jory Lange.

We’re in the middle of another romaine lettuce E. coli O157:H7 outbreak.

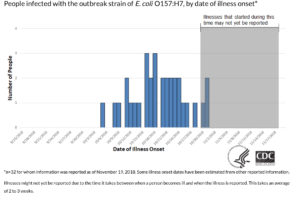

In its initial report, the CDC has identified 32 confirmed cases.

Table courtesy of CDC

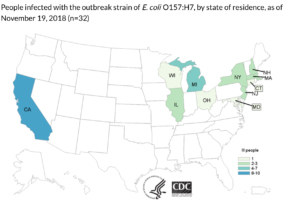

So far, people are sick in 11 states. This outbreak has already hospitalized 13 people, 1 of whom has developed a type of acute kidney failure called hemolytic uremic syndrome or HUS.

Map courtesy of CDC

Like previous romaine lettuce E. coli outbreaks, people are also sick in Canada.

In Canada, there are 18 confirmed cases. 6 Canadians have been hospitalized. And 1 person in Canada has developed hemolytic uremic syndrome.

| Country | United States | Canada |

| Number of Confirmed Cases | 32 | 18 |

| Number of People Hospitalized | 13 | 6 |

| Number of People with HUS | 1 | 1 |

| Number of Deaths | 0 | 0 |

| States/ Provinces Affected | CA (10), CT (1), IL (2), MA (2), MD (1), MI (7), NH (2), NJ (3), NY (2), OH (1), WI (1) | Ontario (3) and Quebec (15) |

| Date Range of Illnesses | October 8, 2018 to October 31, 2018 | Mid-October and early November 2018 |

| Recall? | No | No |

FDA investigators are searching for the source of the latest romaine lettuce E. coli outbreak. A county Agricultural Commissioner in California says that California may be the source. Monterey County Agricultural Commissioner Henry Gonzales says that the October 8 to October 31 illness onset period in the latest romaine lettuce E. coli outbreak fits with the romaine lettuce growing season in California’s Monterey and San Benito counties. “The lettuce most likely came from Monterey County, maybe San Benito County,” he says.

If the latest batch of E. coli-tainted romaine lettuce did, indeed, come from California, it would help explain something else. It would help explain why the strain of E. coli O157:H7 that is getting people sick in this outbreak is different from the E. coli outbreak strain from Yuma, Arizona lettuce that got people sick earlier this year.

The FDA reports that, “Genetic analysis of the E. coli O157:H7 strains tested to date from patients in this current outbreak are similar to strains of E. coli O157:H7 associated with a previous outbreak from the Fall of 2017 that also affected consumers in both Canada and the U.S. The 2017 outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 was associated with leafy greens in the U.S. and romaine in Canada. This year, romaine lettuce is the suspected vehicle for both the U.S. and Canadian outbreaks. There is no genetic link between the current outbreak and the E.coli O157:H7 outbreak linked to romaine that occurred in the Spring of 2018.”

If you have romaine lettuce, you should throw it out, says the CDC. The CDC warns that, “Consumers who have any type of romaine lettuce in their home should not eat it and should throw it away, even if some of it was eaten and no one has gotten sick.” Consumers should be cautious about all types of romaine lettuce, including whole heads of romaine, hearts of romaine, and boxes and bags of precut lettuce (including baby romaine, spring mix, and Caesar salad). The CDC recommends that, “If you do not know if the lettuce is romaine or whether a salad mix contains romaine, do not eat it and throw it away.”

Follow the CDC’s warnings. Avoid romaine lettuce. If you have romaine lettuce at home, throw it out. If you are at a restaurant, don’t order anything that contains romaine lettuce.

First, don’t eat any more. It can take several days for E. coli symptoms to manifest themselves. Just because you ate romaine lettuce and haven’t yet gotten sick, it doesn’t mean that the romaine lettuce you ate was safe.

What do you do now? Watch for signs and symptoms of E. coli infection. These symptoms will show within 1 to 10 days after eating a contaminated product:

If you have eaten romaine lettuce, and have any of these symptom, urgent medical attention is recommended. Early medical attention could help reduce the risk of a more severe illness and potential long-term complications.

Researchers have found that bacteria like E. coli are able to stick to produce like lettuce and can sometimes even get inside the fibers of produce so that they cannot be washed off. This means the bacteria has essentially grown with the plant. Experts still strongly suggest that washing produce is still a good idea, as it can definitely reduce the number of bacteria that you are exposed to. But it is important to note that there isn’t a 100% guarantee.

The best thing right now is to listen to the CDC and FDA’s warnings – Don’t Eat Romaine. Don’t eat whole, chopped, cut, mixed, or anything containing romaine for the time being.

If you are concerned about whether your family members would be vulnerable to E. coli during this outbreak, it is advised that you consider some of the following actions.

Not all lettuce is affected in this outbreak.

There are still many wonderful varieties of greens you can keep in your diet. Kale, or instance, is a wonderful substitute for romaine in a Cesar Salad. Want to be daring? Arugula and wild greens are also good choices, with their peppery flavors. Want something milder like romaine? Butter lettuce, iceberg lettuce, and spinach are common, easy to find leafy greens. Want to just try something new, maybe a little more robust? Shave some Brussels sprouts, cut some purple cabbage, or even load up on mustard greens for the time being. Even some bok choy may surprise you.

It was about this time last year we had a similar outbreak of this kind with all too similar details. Two countries: United States and Canada. E. coli linked to leafy greens and romaine. Several states and Canadian provinces affected. We have been here before. In fact, the CDC confirmed yesterday that this new outbreak has the same DNA fingerprint as the E. coli strain found in sick individuals who were linked to the Fall of 2017 outbreak in the United States and Canada.

Can what we know from the 2017 outbreak help us this time?

Let’s recap, shall we?

| Country | United States | Canada |

| Number of Confirmed Cases | 25 | 42 |

| Number of People Hospitalized | 9 | 17 |

| Number of People with HUS | 2 | Unknown |

| Number of Deaths | 1 | 1 |

| States/ Provinces Affected | California (4), Connecticut (2), Illinois (1), Indiana (2), Maryland (3), Michigan (1), Nebraska (1), New Hampshire (2), New Jersey (1), New York (2), Ohio (1), Pennsylvania (2), Vermont (1), Virginia (1), and Washington (1) | Ontario (8), Quebec (15), New Brunswick (5), Nova Scotia (1), and Newfoundland and Labrador (13) |

| Date Range of Illnesses | November 5, 2017 to December 12, 2017 | November and early December 2017 |

| Recall? | No | No |

In Canada, most of the individuals who became sick reported eating romaine lettuce before becoming sick – at home, in prepared salads purchased at grocery stores, restaurants, and fast food chains. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency tested various romaine lettuce samples for the presence of E. coli, but all of the food samples tested negative and no source of contamination was identified for this outbreak.

A similar outcome occurred in the United States. The United States, however, never came out and pointed the finger at romaine. The investigation focused on a general category of “leafy greens” as those interviewed could not pinpoint an exact leafy green they ate that made them sick. 55% of those interviewed, however, confirmed they ate romaine. The joint CDC and FDA investigation was not able to identify a specific type of leafy greens as the source of the outbreak.

The CDC’s final statement on the lack of source was: “Sometimes outbreaks end before enough information is available to identify the likely source. Officials thoroughly investigate each outbreak, and they are continually working to develop new ways to investigate and solve outbreaks faster.” The FDA also commented, “Both U.S. and Canadian investigations did not identify a common supplier, distributor or retailer for romaine lettuce identified by people who became sick.”

So, traceback became the issue in this one. The FDA and the Public Health Agency of Canada worked together with traceback, but cited the lack of specific evidence to link the outbreak to romaine as a barrier to finding the source.

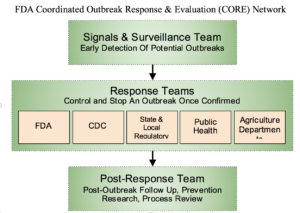

The FDA conducted its normal traceback efforts by:

Photo courtesy of FDA

In the Fall 2017 outbreak, there was no packaging left behind and too many potential suppliers according to the FDA. As the United States and Canada have similar areas where they source romaine products, the FDA determined that the farms that grew the leafy greens were in Arizona, California, and Mexico.

So, what did we learn? Traceback needs to be swift, but that we need to make the system better.

This became obvious when, only a few months later, another romaine outbreak occurred.

With the spring flowers came yet another E. coli outbreak. Again, both the United States and Canada were involved. This time, the culprit was more obvious – romaine was to blame.

But what did that outbreak look like? Could we use what we learned from it, too?

| Country | United States | Canada |

| Number of Confirmed Cases | 210 | 8 |

| Number of People Hospitalized | 96 | 1 |

| Number of People with HUS | 27 | Unknown |

| Number of Deaths | 5 | 0 |

| States/ Provinces Affected | AL (3), AK (8), AR (1), AZ (9), CA (49), CO (3), CT (2), FL (3), GA (5), ID (12), IL (2), IA (1), KY (1), LA (1), MA (4), MI (5), MN (12), MS (1), MO (1), MT (9), NE (1), NJ (8), NY (11), NC (1), ND (3), OH (7), OK (1), OR (1), PA (24), SD (1), TN (3), TX (4), UT (1), VA (1), WA (8), WI (3) | British Columbia (1), Alberta (1), Saskatchewan (2), Ontario (3), and Quebec (1) |

| Date Range of Illnesses | Early March 2018 – June 6, 2018 (Although the FDA reports the last illness was August 2, 2018) | March and April 2018 |

| Recall? | No | No |

The FDA reported the last of the infected romaine was shipped on April 16, 2018.

In the end, the FDA, CDC, and state health departments confirmed that traceback investigations pinpointed the source of contamination to the Yuma growing region. The traceback identified 36 fields on 23 farms in Imperial County, California and Yuma County, Arizona as the suppliers of romaine lettuce that was potentially contaminated and consumed during the outbreak. With the exception of one instance (where the FDA was able to link the Alaska illnesses to a single farm), it was not possible to determine which of the farms was fully responsible for the contaminated lettuce.

Despite finding the locale (or general locale) of the source, the big question remained: what contaminated the lettuce?

Once the season closed, the FDA sprang into action. From June through August of 2018, the FDA and its partners conducted an environmental assessment on the farms in the Yuma growing region. Areas of focus on these farms included, but were not limited to:

The team collected environmental samples, 3 of which were found to contain E. coli O157:H7 with the same rare genetic fingerprint (by whole genome sequencing) as that which made people sick. The FDA determined that the 3 matching samples came from a 3.5 mile stretch of an irrigation canal near Wellton in Yuma County. This canal delivers water to farms in the area (including several of those identified in the FDA’s traceback investigations). Sadly, due to the timing, there were no food products to sample.

Three weeks before the announcement of the new Fall 2018 outbreak, the FDA released its findings on its environmental assessment for the Spring 2018 outbreak. The FDA issued a letter to its local partners in California and Arizona about its concerns, and commented: “Bold action is needed to prevent future outbreaks, especially ones of this magnitude, and to restore consumer confidence in the safety of leafy greens available on the market.”

The FDA offered sound recommendations for how we can prevent these outbreaks in the future. In a nutshell:

(1) growers need to prevent contamination of their crops;

(2) the leafy greens industry needs to invest in research on how to prevent contamination;

(3) traceback needs to be better and faster;

(4) surveillance testing and sampling is to be done on romaine lettuce; and

(5) if adulterants are found, swift discussions with produce processors will commence.

The FDA also intends to “explore regulatory options and consider appropriate enforcement actions against firms and farms that grow, pack, or process fresh lettuce and leafy greens under insanitary conditions.”

The question is now, what does this mean for the current outbreak? Let’s hope we are not walking in circles.

It means that (perhaps) we have a starting point. Last time, the FDA was not able to conduct regulatory inspections and observe the manufacturing and processing of romaine at all fresh-cut produce manufacturing/processing facilities they found. Why? Because “many of the facilities were not in operation due to the end of the growing season and the manufacturing/processing equipment that may have been used was no longer available for inspection” according to the FDA. Hopefully, quick action will get some sampling done of the products while they are still in the season.

The FDA now has the contact information for all of the previous farms and processors in the Fall 2018 outbreak. Surely, they can contact all of them and go on a swabbing spree? I mean, several food manufacturers have already understood that FDA “swab-a-thons” are a necessary evil, so why not the farms? The resolution is not as simple as this.

This brings me to a bigger than big question: are we dealing with the same farms here? The Yuma growing season is supposedly between November and March. Imperial County, California’s growing season appears to be late November through March. But the illnesses in this outbreak are in October. Where is romaine grown in September and October?

Not Yuma, Arizona. It is grown in Salinas County, California, who’s growing season is from late March through early November.

In fact, in 2017, Monterey County produced more than 40 million cartons of romaine lettuce –which accounted for more than half of total leaf lettuce production in the county. According to Monterey County Agricultural Commissioner Henry Gonzales said “the date of the 32 reported illnesses — from Oct. 8 through 31 — corresponds with the romaine lettuce season in Monterey and San Benito counties.”

It was too late last time for the FDA to get produce samples from Salinas County farms. No produce was left. Also, no environmental assessment has been conducted in Salinas County by the FDA. So, it is likely they will need to investigate Salinas County with the fine-toothed comb they did to Yuma this year.

Many experts, including Sylvain Charlebois, a researcher in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University in Canada, was surprised at how long it took anyone to issue a recall during the last Fall 2017 outbreak. He pressed that it was “unusual for an outbreak to go on for more than a week without a recall being issued.” Charlebois and others confirm that better traceability systems are clearly needed for produce in order to narrow down the source.

Look, Manufacturers’ supply chains are complicated. A supply web would be a better comparison than just a chain. There are just so many stops in the journey from farm to plate. There complex sequences of moving parts that can make full transparency challenging. Blockchain technology makes it easier for the users to track all the transactions simultaneously and in real time.

Blockchain, in simple terms, can be put as a way of storing and sharing information across a network of users in an open virtual space. So, any food retailer or manufacturer would be able to know who the supplier has dealt with in a matter of few seconds. And since, transactions are stored at multiple spaces, it is almost impossible to hack and manipulate the system. Due to these reasons and many others, blockchain can easily empower the entire food chain to be more responsive (and responsible) in any foodborne illness outbreak.

Walmart’s implementation of this technology has already proven that traceback that previously took several days to weeks could be done in seconds. Without this technology, a product that changes hands many times takes time to sort through supply chain data. That same information could be at an investigator’s fingertips in the time it takes to generate a search query. This means, outbreaks like this one need not jump to over 200 cases and recalls can be initiated in a quick and efficient manner.

Charleboois and other food safety experts support blockchain implementation systems for grocers where distributors can share digital data to track the supply chain system. “So, when you have a situation like this, if you are using a new technology, you can trace problems very quickly,” he adds. “But now we have a case where traceability is probably an issue … I would say the weakest aspect of our food safety system is traceability.”

This frustrating thing about this is that we keep seeing this over and over again. The FDA has been sending its warning letters to the leafy greens industry since 2004, asking them to get their act together concerning leafy greens outbreaks. It’s been 14 years! A 2015 study showed that 606 outbreaks of foodborne illness were linked to leafy greens. The FDA reports that, between 2009 and 2017, 28 of those outbreaks were linked to STEC Ecoli infections.

What do these numbers really look like? Here is a concerning table of those outbreaks linked to Ecoli illnesses created by the food safety geniuses over at Barf Blog, Dr. Ben Chapman and Dr. Doug Powell (Fall of 2018 outbreak omitted) between 1995 and 2017.

| Date | Causative Agent | Illnesses Reported | Source |

| Nov. 2017- Dec. 2017 | E. coli O157:H7 | 41, 1 death | romaine lettuce |

| Apr. 2015 | Escherichia coli, Shiga toxin-producing | 7 | prepackaged leafy greens |

| Mar. 2015 | E. coli O157:H7 | 12 | leafy greens |

| Jul. 2014 | E. coli O111 | 15 | Salad/cabbage served at Applebee’s and Yard House (Minnesota) |

| Oct. 2013 | E. coli O157:H7 | 33 | Pre-packaged salads and sandwich wraps (California) |

| Jul. 2013 | E. coli O157:H7 | 94 | Lettuce served at Federico’s Mexican Restaurant |

| Dec. 2012 – Jan. 2013 | E. coli O157:H7 | 31 | Shredded lettuce from Freshpoint, Inc. |

| Oct. 2012 | E. coli O157:H7 | 33 | Leafy greens salad mix (Massachusetts) |

| Apr. 2012 | E. coli O157:H7 | 28 | Romaine lettuce |

| Oct. 2011 | E. coli O157:H7 | 58 | Romaine lettuce |

| Oct. 2011 | E. coli O157:H7 | 26 | Lettuce |

| May 2010 | E. coli O145 | 33 (26 lab-confirmed) |

Romaine Lettuce grown in Arizona |

| Nov. 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 130 | Romaine lettuce |

| Oct. 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 2 | Chopped shredded iceberg lettuce (Michigan) |

| Oct. 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 43 (Johnathan’s Family Restaurant), 21 (Little Red Rooster Restaurant), 12 (M.T. Bellies Restaurant) | Lettuce |

| Aug.-Sep. 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 74 | Lettuce from Aunt Mid’s Produce Company (California) |

| Aug.-Oct. 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 13 | Spinach (Oregon) |

| May. 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 10 | Prepackaged lettuce |

| May. 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 6 | Pre-packaged salad |

| May 2008 | E. coli O157:H7 | 9 | Lettuce (California, U.S.) |

| Jul. 2007 | E. coli O157:H7 | 26 | Lettuce |

| Nov. 2006 | E. coli O157:H7 | 78 | Lettuce |

| Oct. 2006 | E. coli O157:H7 | 205 | Pre-packaged baby spinach from Dole Food Company (California) |

| Sep. 2005 | E. coli O157:H7 | 34 | Prepackaged bagged lettuce from Dole Food Company |

| Oct. 2005 | E. coli O157:H7 | 12 | grapes, green; lettuce, prepackaged |

| Nov. 2004 | E. coli O157:H7 | 6 | Lettuce, unspecified |

| Nov. 2003 | E. coli O157:H7 | 19 | Spinach, unspecified |

| Oct. 2003 | E. coli O157:H7 | 16 | Spinach, unspecified |

| Sep. 2003 | E. coli O157:H7 | 51 | Lettuce-based salads, unspecified |

| Nov. 2002 | E. coli O157:H7 | 60 | Romaine lettuce |

| Jul. 2002 | E. coli O157:H7 | 32 | Romaine lettuce from Spokane Produce (Washington) |

| Jul. 2002 | E. coli O157:H7 | 55 | Caesar salad |

| Nov. 2001 | E. coli O157:H7 | 20 | Lettuce-based salads, unspecified |

| Oct. 2000 | E. coli O157:H7 | 6 | Salad |

| Oct. 1999 | E. coli O157:H7 | 45 | Lettuce, salad |

| Oct. 1999 | E. coli O157:H7 | 47 | Salad |

| Sep. 1999 | E. coli O157:H11 | 6 | Lettuce |

| Sep. 1999 | E. coli O111:H8 | 58 | Salad |

| Feb. 1999 | E. coli O157:H7 | 72 | Lettuce |

| May 1998 | E. coli O157:H7 | 2 | Salad |

| May 1996 | E. coli O157:H7 | 61 | Lettuce |

| Oct. 1995 | E. coli O153:H46 | 11 | Lettuce |

| Sep. 1995 | E. coli O153:H47 | 30 | Lettuce |

| Sep. 1995 | E. coli O157:H7 | 21 | Lettuce |

| Jul. 1995 | E. coli O153:H48 | 74 | Lettuce |

Consumers ask really good questions. One of these is: how does E. coli contaminate lettuce?

It all comes down to the farm. STEC E. coli contamination of leafy greens has been identified in the past by traceback to most likely occur in the farm environment – through animal vectors or contaminated water irrigation. According to the FDA:

“Contamination occurring in the farm environment may be amplified during fresh-cut produce manufacturing/processing if appropriate preventive controls are not in place. Unlike other foodborne pathogens, STEC, including E. coli O157:H7, is not considered to be an environmental contaminant in fresh-cut produce manufacturing/processing plants.”

Essentially, any of the following can occur:

Lettuce, like many other crops, is grown in the ground. If the seeds have been watered with contaminated water or fertilized with contaminated manure, the plant grows with the bacteria. The bacteria live and grow in the root system, in the leaves, and in the plant itself.

Last year, Big Produce got pretty upset about the bad press surrounding these outbreaks. But our response to that is simple: if Big Produce is unhappy with the bad press, perhaps they should do something about it. The FDA has already pressed for more testing and funding for research, instead of just “cooperating with federal agencies,” how about they use the fancy technology they already have access to, and begin publishing the negative results. Maybe even assist the CDC and FDA in its investigations? Maybe help with testing of lettuce products? Self-identifying could lead to the responsible party revealing themselves.

Once the source is identified, it will allow a more pointed recall and an opportunity to mitigate the contamination. This turns a lose-lose into a win-win situation. So, instead of demanding an outbreak be over – help out to figure out the mystery. Then, at least, it will be over. And maybe, just maybe, we can keep this from happening over and over again.

Ecoli is a bacterium found in the intestines of mammals – human and others alike. Many forms of E. coliare harmless, though others can cause serious illness including diarrheal illness and even urinary tract infections, respiratory illness, bloodstream infections, and other illnesses associated with the bacteria making its way out of the intestines.

Some E. coli bacteria can produce a toxin known as Shiga toxin. These are called STEC E. coli. These bacteria can cause serious illness and responsible for most illness causing E. coli infections. The CDC estimates that STEC is responsible for about 265,000 illnesses each year in the United States. This estimate includes about 3,600 hospitalizations, and 30 deaths.

Symptoms of STEC range from mild to severe and life-threatening. They could include terrible stomach cramps, diarrhea (potentially bloody), and vomiting. Fevers are generally less that 101 ºF if present. Many affected people get better within 5 to 7 days.

While STEC can infect anyone and cause serious illness, the very young and the very old are more likely to develop additional serious illness. Children under the age of 5 years old are at risk for developing a kidney affecting condition called hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS).

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli or STEC is the cause of most outbreaks involving E. coli in the United States. More specifically, E. coli O157:H7 often shortened to E. coli O157 and even simply O157. All other STEC are lumped into the category of “non-O157”. STEC E. coli are the very dangerous ones, that coincidently are also the cause of this very outbreak.

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, or HUS, affects somewhere between 5 and 10% of those who have been diagnosed with E. coli O157. This is a bacterial toxin inducing form of kidney failure. Those with HUS may experience less urination, loss of the pink color inside the lower eyelids and cheeks, and feel very tired. While most people with HUS recover within just a few weeks, others can suffer permanent health problems or may even die. Those with HUS should be hospitalized to closely monitor kidneys as they may stop working and other serious health problems that could result from the illness. If you or a loved one developed HUS from food contaminated with E. coli, speak with our hemolytic uremic syndrome attorney.

It’s hard to determine if what you are experiencing is just a bit of stomach upset or a viral bug or part of a multistate-outbreak. We recommend that, if you are showing any of the symptoms of an Ecoli infection after eating romaine lettuce, seek immediate medical attention.

The CDC recommends contacting your healthcare provider if you experience diarrhea that lasts for more than 3 days or diarrhea that is accompanied by blood in the stool or high fever. If you are vomiting so much that you cannot keep down fluids and as a result you are not passing very much urine, you are extremely dehydrated and should seek medical attention.

Anyone involved in the chain of distribution of the product can be liable for any damages. This includes the processing company or manufacturer, the supplier or distributor, and the retailer (such as a restaurant or grocery store).

If you have been diagnosed with Ecoli, negligent food preparation, manufacturing, or serving practices may be to blame for your suffering. A company that breaks safety rules and causes harm needs to be held liable for their negligent actions, not only to account for the damage they have already caused, but to also prevent future illnesses. You have the right to seek compensation from the liable party(ies) for your medical expenses, current and future lost wages, as well as for your pain and suffering. Consult with a Ecoli lawyer to discuss your case and get started on your claim.

If you believe you have developed an Ecoli infection from eating romaine lettuce, we want you to know that our Ecoli lawyer at the Lange Law Firm, PLLC is currently investigating this matter and offering free legal consultations. Our lawyer, Jory Lange became a lawyer to help make our communities and families safer.

If you or a loved one have become ill with Ecoli or if you would like to get information about a romaine lettuce E coli outbreak lawsuit, you can call (833) 330-3663 for a free legal consultation or complete the form here.